The duty of the ranger was also to write up all the collected and polished amber into a stitched book stating its weight, put it into a box and lock it. Then the amber had to be transferred to the customs controller via register and then it was send to the governor or the district once a month. The latter had to send the big pieces to the scar’s collection and the small ones – to the Curronian treasury for public sale.

On the separate paragraph of the Rules it is said that no amber master could get near the beach. With “those people” the seashore bureaucrats had no right to communicate or make business. The Rules also prohibited the purchase of amber and didn’t allow Jews to live on the seashore. For breaking of this prohibition a 100 rouble or bodily penalty was designated.

According to the Rules the control of amber mining belonged to the clerks and the gathering of amber from the sea and the dunes was the seashore peasants’ and fishermen’s duty. They had to work day and night according to the orders of the seashore rangers and other supervisors. In the fon Shneiders Rules there’s no mentioning of payment size that the peasant should receive for his work. But threatening with penalties is in many paragraphs. The peasants were punished by fines and physical penalties for one taken small piece of amber. At the same time the bureaucrats who did the same offence could only lose their job.

The seashore peasants and their grown-up sons were force to wow that they’ll collect the amber and give it all to the government. The father had to wow that “my wife, children or someone else won’t take even the smallest piece of amber either seen or under cover”. And when the son got to the age of 18, they had to wow that “if I see or notice that my father, mother, brothers, sisters, masters, workers or other people abuse or are preparing to abuse the amber Rules, I wow not allow them to do so and won’t pander”.

So the peasants won’t forget their wows, the Statute expressed a desire that seashore pastors twice a year – on a Sunday after St. Martin’s day and at the end of March – would preach to them and call the peasants to keep to the wows of amber gathering.

The interesting thing is that the biggest reward or punishment for a seashore peasant was either exception from military service or writing into the recruits. “The most effective way to prevent the seashore peasant faking is such: the peasants who collect the amber will be exempted from military duty and if one appears to have stolen, he’ll be given to the parish recruits first of all”.

Palanga belonged to Curronian province. In the Statute it is said that the seashore guards should live “where the amber mining is the most profitable, for example, in Palanga”. The writer of the Statute regretted that Palanga amber customs is private and all its profits go to the owner and not to the government. Worry is also expressed here that sub-buyers get profits from amber as well. It is written that “30 years ago one sub-buyer Jew, the heir of Masalskis, paid 200 tithes only for the right to buy amber from peasants” and he “bought amber for half price, so during a year he would buy amber for 1000 or even 2000 tithes, and on other years for 4000-5000 tithes”.

The archive documents clearly state that the regalia introduced not only in Prussia, but also in Curronia closed ways for amber to get into the folk way of life.

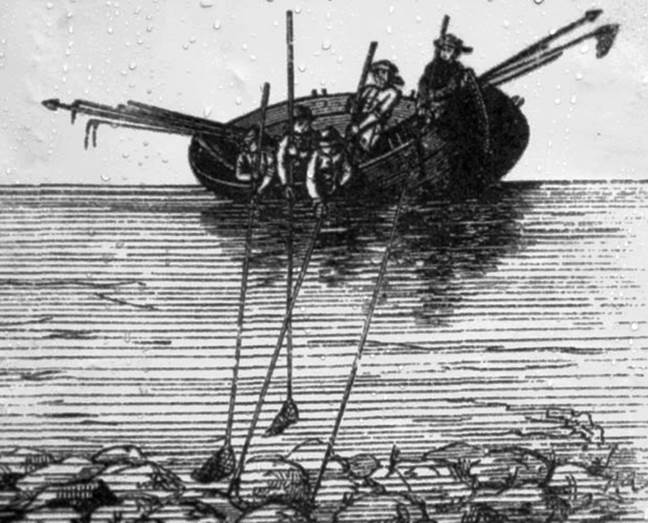

XVII century gravure shows how the fishermen light up and hoist a tar barrel high up a tree to light up the bottom of the sea so it’s easier to search for amber. Though, this way was very dangerous when the sea was very wavy – the returning waves could drag to the sea not only the whole catch but the catcher himself. So this method isn’t used anymore.

EN

EN LT

LT